In attempting to define Revolution, we are faced with a great challenge. The concept of revolution encompasses thousands of years, hardships and struggles, major and minor moments in history, many victories, and difficult losses. Traditionally, a revolution is defined as a drastic overthrow of a corrupt or failing government by the people who inhabit the country. However, it is so much greater than simply that. Revolution is people banding together, proclaiming that they have had enough. It is the realization that there must be something greater for each person, the person who only wants the best for themselves and their people. People have put aside differences, whether religious, ethnic, racial, or economic, and come together to change their current conditions. They refuse to live in silence and accept these horrific circumstances. The average, every day person is often overlooked. We see them as a reflection of the ruling government, yet fail to see the humanity and life in each one. These people seek a life of safety and security, a life without worry of death, just as we all do.

There are two fundamental aspects to a revolution: physical revolution and revolution of mind. The physical revolution is the act of revolting, the embodiment of it. It is the physical actions, protesting, marching, or fighting back against the military sent to quiet voices. The revolution of the mind is the change of thought, perspective, or beliefs. The breaking down of beliefs that are no longer sustainable, and the creation of new beliefs aimed towards each new generation. Together, these two aspects define revolution and its manifestation in our world.

In Unit 1, Locke details each person’s inalienable rights: life, liberty, and private property. He argues that all people are equal and are equipped with free will and reason. He defines private property as our physical bodies, and explains that the ability to work is solely our own. He relies heavily on revolution of the mind to explicate these concepts.

Unit 2 discusses a different type of revolution: scientific. A scientific revolution is a paradigm shift, a fundamental change in approach or underlying assumptions. A revolution in science is a matter of the replacement of paradigms. Copernicus and Ptolemy studied the physical revolutions of the sun and argued either a heliocentric or geocentric model of the universe, respectfully. Similarly to Locke, this type of thought invokes the revolution of the mind.

Unit 3 explores the horrors of the Rwandan genocide and the response of the outside world to those tragedies. Gourevitch, a well-renowned journalist, visits Rwanda after the genocide, interviews survivors, and collects the stories into a book, We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families. Gourevitch revolutionized the way journalism portrays Rwanda, the Rwandan people, and the genocide itself. Traditionally, journalists state facts and do not include personal testimonies, meanwhile, Gourevitch took the time to learn from the people who suffered and portray those events in his work. He aided in changing the western view of the genocide and Rwandans.

Unit 4 discussed the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950-60s and the steps taken to achieve this great revolution. Black Activists called for a systemic change, a revolution of belief and process. They used physical actions, such as sit-ins, marches, and protests to convey their message and continued to push until people began to change their beliefs. The Civil Rights Movement utilized both physical revolution and revolution of the mind to achieve their end goal, and through constant and tenacious efforts they made great stride in changing the world.

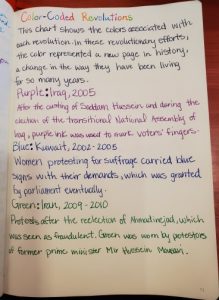

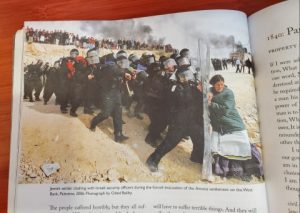

Lapham’s Quarterly also presents many different instances of revolution portrayed through different mediums. I focused on “Today’s Life and War” by Gohar Dashti, which depicts a man and woman sharing a meal seated at a table with a tank aimed at them in the background. The work speaks to the fact that war and conflict permeate all aspects of society. While war rages on the battle fronts, every day people continue to live life. Seated at the dinner table, a rather mundane activity, they worry about the dangers of war surrounding them. This image also depicts the way in which revolution permeates every aspect of your life. To really create change, the desire for it must be found everywhere, even in your daily activities. Similarly, the image of the Jewish settlers clashing with the Israeli officers shows people simply fighting for a chance to live, to be valued as people, not as objects of war. Finally, “Color Coded Revolutions” shows the impact of colors in a revolutionary act. Each color represents action taken by the people to change their future, standing up and calling for an end to the injustice.

Unit 5 takes a creative and physical approach to Revolution. While many of the revolutions we have studied thus far have been political or social, dance movements, as we learn in this unit, have also played revolutionary roles. Counterfactual thinking wants you to “consider the probable, plausible, or possible consequences of an admittedly false conditional.” Similar to counterfactual thinking, counterfactual movement asks you to consider, in mind and body, the effects of bodily self-expression on the greater scheme of society. For example, Bill T. Jones, in his work “Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” and Camille A. Brown’s “Black Girl Linguistic Play,” use dance as a way to reclaim a lost culture in an effort for empowerment. A physical revolution, through dance, can effect people on a more personal level, through movement and testament.

Unit 6 brings us another creative interpretation of revolution. For centuries, art has a form of personal revolution. Artists used it as a way to change the perspective of many societies. Unit 7 focused on Reductionism in Art and how revolutionary used their art for certain purposes. Often, people compare the Arts to the Sciences, however, few acknowledge that they may have more in common than given credit for. Chuck Close, the artist I presented on, used a technique called photorealism, in which he would take photographs and paint each grid in abstract shapes and colors. Up close, the painting was simple a random combination of shapes and colors, but from afar, they painting came together to be a portrait. Movements such as this teach us that perhaps not everything is as it seems. Artists present us with a secondary lens with which to view the world. A revolutionary outlook on life.

Unit 7 takes us to Russian revolutions and Stalin’s terror. The reign of Stalin brought fear over the country of Russia. The uncertainty created a distrust between family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers. Citizens were brainwashed to follow Stalin’s regime, following any and all laws, regardless of how just or unjust. No one could be trusted, anyone could report you for anti-government actions, regardless of the truth. Ordinary people were executed, deported, or disappeared. While we usually associated revolution with victory, for many Russians, these revolutions only worsened conditions. Not all revolutions, we learn, are good and just. Unit 8 poses another violent revolution, involving Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction. Ulrike Meinhof was a far-left West German militant who in pursuit of taking down a corrupt government, took a violent approach and hurt many people along the way. Her group, the Baader-Meinhof group, was an openly violent resistance group, which attempted to fight a war that had no winners. Meinhof became a terrorist, even going to the extent to attempting to enroll her young daughters in a terrorist training camp. This also poses the question, does a revolution have to be successful to be considered a revolution? Is the act enough to validate a claim of revolution, or should a victory claim revolution?